Music for iOS by Norbert Herber

Created with AudioMulch, Max for Live, Absynth, Massive, Wwise, Unity, C#, Xcode, Fisher-Price “Ocean Wonders Soothe and Glow Seahorse”

Headphones or a quiet amplification system are recommended. Connect your iPhone/iPad to a stereo or smart speaker and listen while writing, thinking, or falling asleep. Due to technical limitations in development tools, this app cannot play in the background while you use other apps.

Support

Contact me with questions or to get help with Br2.

In 1996 Brian Eno invented the term generative music to describe an ambient sound experience that is unique upon every encounter. Simple compositional rules unfold and shape the music’s moment-to-moment character within a range of possibilities. This app uses the processing capabilities of your device to create continuous music that drifts within different moods and is unlikely to repeat.

Machines for Music: A condensed history of Generative music

Generative music is much like the music of wind chimes. Given the potential complexity of some generative music systems, the comparison could seem overly simple, but it is accurate. Wind chimes have an elegant simplicity that captures the essence of generative music and allows one to extrapolate the ways in which such a system could work at larger scales. Alan Dorin writes that wind chimes have earned

…a special place in the history of Generative music. Note that the wind-chime’s structure dictates the timbres and pitches that it is capable of creating. Although it is capable of producing an infinite variety of sound-events, it may not produce any timbre or sound-event. [6]

The “infinite” that is so often discussed in generative music is not endless in every sense of the term. In these works, infinite may characterize the potential length of performance or the perceived variety of melodic and textural development. It does not suggest that comprehensive musical knowledge has been encoded as a simple computer program that will spin out tune after tune in any style. Music, like all of the arts, benefits from constraints and limitations. These have the counterintuitive ability to increase creative potential and variety. While wind chimes are perhaps an extreme case of creative economy, they show that there can be a seemingly infinite variety of beauty and interest produced through very simple means. Other (non)musical precursors reveal this in different ways as a result of their strengths and productive limitations.

In 1972 Cybernetician Stafford Beer defined an algorithm as “a comprehensive set of instructions for reaching a known goal” [2], but the idea was first introduced in the ninth century by Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khowarizmi [4]. Composers have been employing algorithms since the 1026. Guido d’Arezzo (995-after 1033) developed a systematic means to pair pitches with the vowel sounds in the words of a liturgical text [14],[17]. Years later, Philippe de Vitry (1291-1361) [4], Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377), and Guillaume Dufay (1400-1474) [17], are all known to have used algorithmic techniques in various ways to combine the rhythmic, pitched, and textual material of motets. In 1660 Giovanni Andrea Bontempi wrote New Method of Composing Four Voices, by means of which one thoroughly ignorant of the art of music can begin to compose, in which he proposed various systematic means of composition for, as the title suggests, uninitiated musicians [4]. In the eighteenth century Mozart is often the most-recognized for composing Musikalisches Würfelspiele (musical dice games), but Haydn, C.P.E. Bach, and Johann Philipp Kirnberger [4] were also involved in composing these chance-based, musical parlor games.

David Cope, a composer and expert on Algorithmic music, continues his historical discussion of algorithmic precedents in western art music to include Johann Joseph Fux, whose rules regarding counterpoint were influential to Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, among others [4]. He cites many other musical situations where an algorithm or some system of constraints has been employed in nearly all forms of composition leading up to the modernist, serial approach of Pierre Boulez and the aleatoric techniques of John Cage. Cope advocates an inclusive perspective, and considers indeterminate techniques, compositions created on performance instruments, and the rules of music theory all to be a kind of algorithm.

Beer’s definition of an algorithm includes, “…a known goal,” which means the destination or result of a process is specified at the outset of the operation. This definition speaks to the written musical work itself. It reflects the historical context of these techniques within western art music, and situates algorithmic composition as one “musical species” evolved from the seminal pieces identified here. In his book, The Brain of the Firm, Stafford Beer makes a clear distinction between algorithm and heuristic, which he defines as “a set of instructions for searching out an unknown goal by exploration, which continuously or repeatedly evaluates progress according to some known criterion” [2 emphasis added]. Beer writes that if you were to help someone reach the top of a cloud-covered mountain, the heuristic “keep going up” [2] will get them there.

While algorithms can be a part of Generative music, there is often more involved in the process. Strict algorithmic techniques certainly set the foundation for some of the qualities that make Generative music what it is, but the trial and error of a heuristic approach also has great value while the seed of a new work is being created. Beer’s definitions, and the differences he draws between algorithm and heuristic were outlined by Brian Eno in his essay Generating and Organizing Variety in the Arts as a means to help distinguish the differences of approach between traditional western art music and Experimental music. His observations serve as an excellent pivot-point in the history of Generative music.

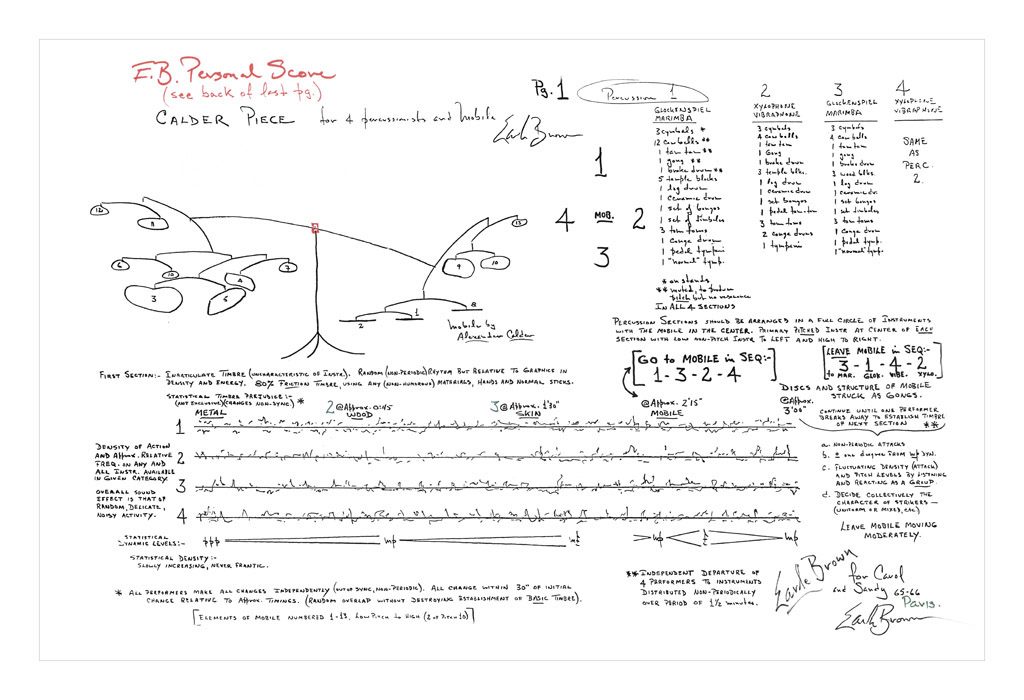

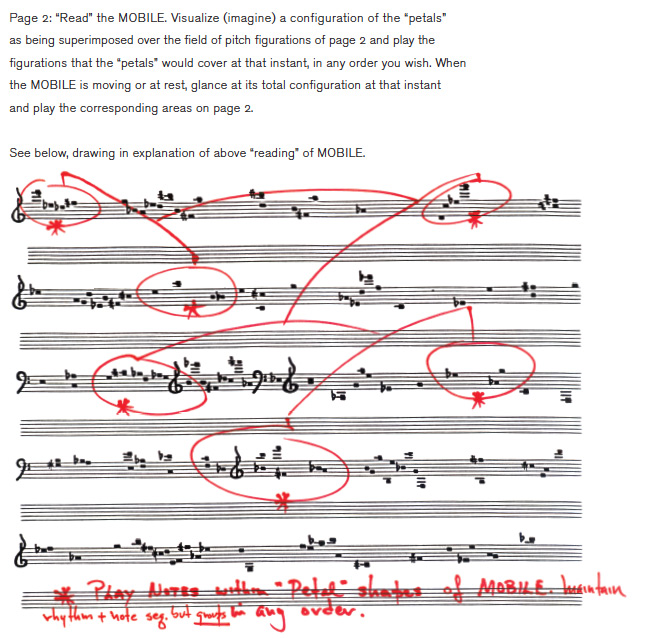

Experimental music emerged from New York in the 1950s as “sound come into its own” [3]. In this movement, musicians John Cage, Morton Feldman, Earle Brown, and Christian Wolff shared a common determination

…for a music which should be allowed to grow freely from sound at its very grass roots, for methods of discovering how to ‘let sounds be themselves rather than vehicles for man-made theories, or expression of human sentiments.’ [3]

Cage and those listed above were significant in getting the ideas behind Experimental music started. Other musicians working in England, such as Cornelius Cardew, Gavin Bryars, and John Tilbury, were able to move some of these ideas out of traditional “music” performance venues and into art schools, galleries, and other accessible public places [12]. Brian Eno, then an aspiring art student who experienced this dissolution of austerity first-hand, comments that this music was “…explicitly anti-academic…” in order to counter the more cerebral serial music of Stockhausen and Boulez that was currently the rage with other students from the nearby music college [12]. In some cases these works were admittedly written for non-musicians [12], but this music was in no way overly simple or pedestrian. Rather, as Cage expressed, it granted sound, performers, and listeners a great deal of freedom. The procedures of creation and the processes musicians and audiences experienced during performances of these works were far more important than any sort of artifact or product.

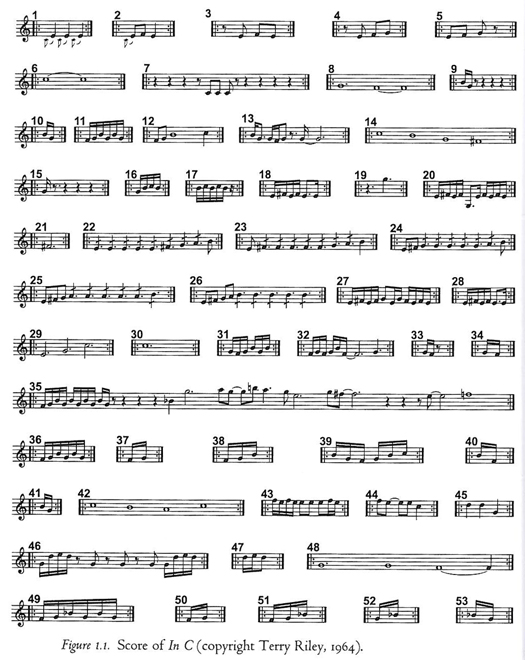

In C by Terry Riley

Terry Riley’s In C [13] is a seminal work in both the Experimental and Minimalist music traditions. The piece consists of 53 melodic phrases (or patterns) and can be performed by any number of players. The piece is notated, but was conceived with an improvisatory spirit that demands careful listening by all involved in the performance. Players are asked to perform each of the 53 phrases in order, but may advance at their own pace, repeating a phrase or a resting between phrases as they see fit. Performers are asked to try to stay within two or three phrases of each other and should not fall too far behind or rush ahead of the rest of the group. An eighth note pulse played on the high C notes of a piano or mallet instrument helps regulate the tempo, as it is essential to play each phrase in strict rhythm [13].

The musical outcome of In C is a seething texture of melodic patterns in which phrases emerge, transform, and dissolve in a continuous organic process. Though the 53 patterns are prescribed, the choices made by individual musicians will inevitably vary, leading to an inimitable version of the piece every time it is performed. Riley’s composition reflects one of John Cage’s thoughts on Experimental music, when he writes that the “experiment” is essentially a piece of music: “the outcome of which is unknown” [3]. When performed, In C has indefinite outcomes and yet—like wind chimes—is always recognizable as In C due to the character of the musical material and instructions that make up the work (its composition).

Free and non-idiomatic improvisation [1], games-based improvisation [19], and other forms where personnel choices (who to hire in your group) are enough to constitute a loose set of rules or organization [18] also share some common ideas with Experimental music. But in these forms, human musical intelligence is an essential ingredient of the algorithm. Experimental and Improvised music require performers to listen and respond. Generative music, by comparison, relies on automated processes by which the music can come into its own with minimal signs of human intervention.

The overall aesthetic of Generative music has much in common with the casual, open, restless attitude of Experimental music. As with most histories, the origins of Generative music are fragmented—an amalgam of technologic possibilities and musical precursors. Like the music itself, once these ideas have been blended together, the process of unfolding continues.

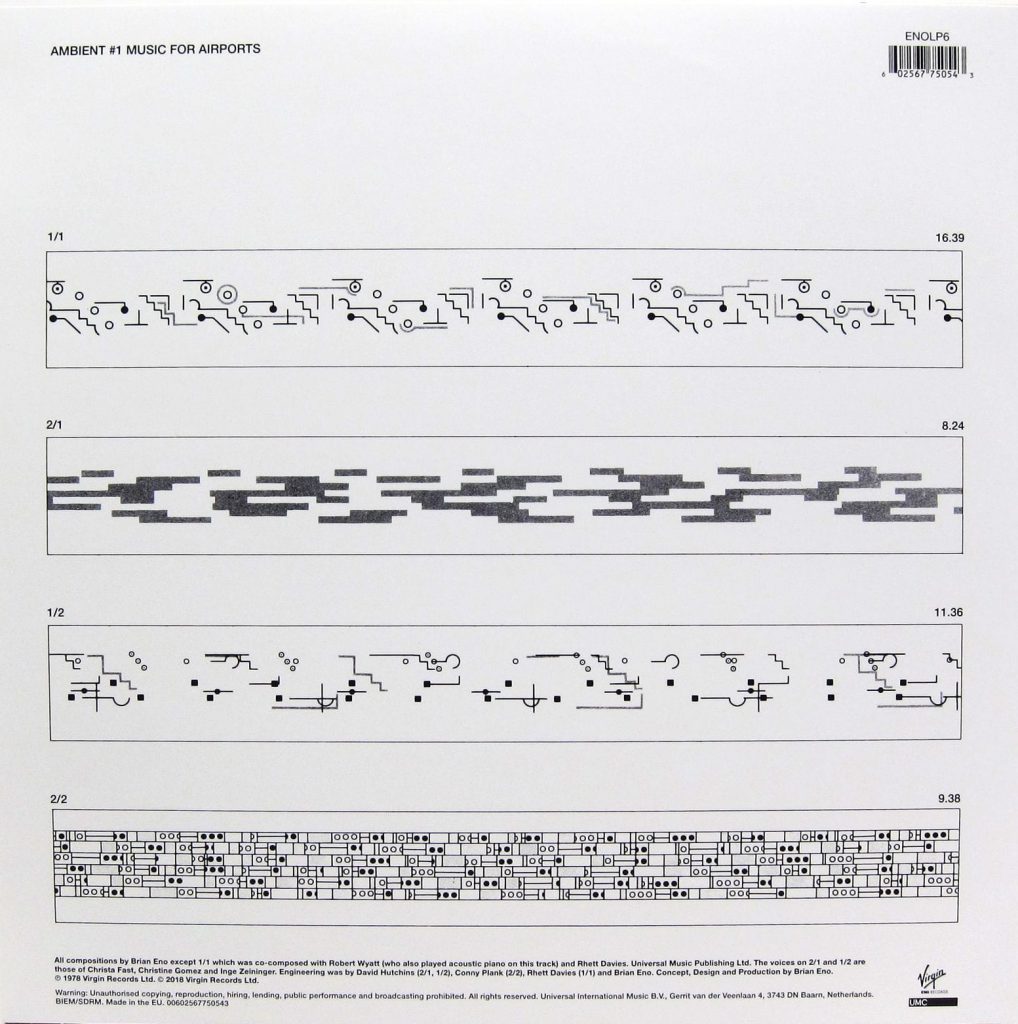

In many ways the history of Generative music mirrors the interests and influences of Brian Eno. Through his recording studio interventions and Oblique Strategy cards, Eno can be credited with transplanting Experimental techniques into Art Rock and popular music [15]. His tape delay experiments with Robert Fripp (1973-1974) and later solo project Discreet Music (1975) furthered an ongoing musical investigation into processes and systems, and among other circumstances, led Eno to pioneer Ambient music. Eno’s first “official” Ambient album, Music for Airports (1978) makes use of tape phase techniques similar to those of Steve Reich in his pieces It’s Gonna’ Rain and Come Out. Eno commented that It’s Gonna’ Rain is

probably the most important piece that I heard, in that it gave me an idea I’ve never ceased being fascinated with—how variety can be generated by very, very simple systems. [16]

The idea of a music-making machine has fascinated Eno throughout his career [5],[8]. Tape delay and phase systems mark the beginning of this ongoing process in his body of work. In the years that followed, while working in a more conventional art setting with video and light installations, he used looping cassette tapes to create a continuous, ambient sound world that could be heard throughout the environment where his work was experienced. With the standards set by contemporary digital technology, cassette players seem primitive. But they echo the incredible “variety through simplicity” idea from Reich’s work that was so initially inspiring.

The term generative is most closely connected to Eno’s work with Koan, a software application for composing Generative music. Eno’s only Koan-based album was titled Generative 1 [9]. Koan (and Noatikl, its successor), have not gained much popular momentum as music production tools, but the techniques and aesthetics these applications enabled has come to be known broadly as Generative music. In the way that the name Experimental music contains a raison d’être, so does Generative music:

The concepts of process and algorithm are closely linked with those of dynamism and change, with becoming. When a process creates a new entity or brings about novel circumstances, it is a generative process with respect to the change(s) it brings about. Why not explore this concept of change through algorithmic means? [6]

Generative music uses algorithms, but it is not Algorithmic music. For instance, an algorithm used by Eno in Music for Airports follows the instruction: play the note C every 21 seconds. The term generative communicates the idea of a computer processor (or other machine) doing the work to compute the iterative sequences, shifting permutations, and random routines that can also be used in this music. Unlike much Algorithmic music that focuses on producing a final, notated output or a music that can authentically match a predetermined style [4], Generative music can be more aptly compared to a seed. Brian Eno has applied this metaphor in talks and interviews, [10], [17] saying that like a seed, something unique will grow out of this music. Neither the listener nor musician knows exactly what it will be, but just as one would not expect a daisy to sprout from tomato seeds, each has a general idea or range of expectations. A tomato plant will sprout, but it won’t look exactly like the one next to it or like any others in the row. The generative musical experience, like Beer’s destination at the misty mountain top, is there, but the details are uncertain and the ensuing journey rich in possibility.

This essay is excerpted from Amergent Music: behavior and becoming in technoetic & media arts

References

- Bailey, D 1992, Improvisation: its nature and practice in music, Da Capo, New York.

- Beer, S 1972, Brain of the Firm: the managerial cybernetics of organization, Allen Lane The Penguin Press, London.

- Cage, J 1973, Silence: lectures and writings, Wesleyan University Press, Middletown, Conn.

- Cope, D 2000, The Algorithmic Composer, A-R Editions, Inc., Madison, WI.

- Darko, J, 25 July 2009, ‘Artscape – Brian Eno in Conversation’ (Video). Available from: <link>. [5 July 2010].

- Dorin, A 2001, ‘Generative Processes and the Electronic Arts’, Organised Sound, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 47-53.

- Eno, B 1976, Generating and Organizing Variety in the Arts, Available from: <link>. [26 June 2009].

- ________. 1996, A Year With Swollen Appendices, Faber & Faber, London.

- Eno, B & SSEYO 2006, Generative Music 1 by Brian Eno, SSEYO, Available from: <link>. [16 July 2010].

- Eno, B & Wright, W 2006a, Playing with Time (audio recording), Long Now Foundation, San Francisco.

- ________. 2010, ‘Will Wright and Brian Eno Play with Time’ (video). Available from: <link>. [2 September 2010].

- Nyman, M 1999, Experimental Music: Cage and beyond, 2nd ed, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.; New York.

- Riley, T 1964, In C, Other Minds, Available from: <link>. [24 May 2005].

- Roads, C 1996, The Computer Music Tutorial, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

- Sheppard, D 2008, On Some Faraway Beach: the life and times of Brian Eno, Orion Books, London.

- Tamm, E 1995, Brian Eno: his music and the vertical color of sound, Updated edn, Da Capo Press, New York.

- Toop, D 2001, ‘The Generation Game’, THE WIRE, no. 207, pp. 39-45.

- Warburton, D 2005, ‘Les Instants Composés’, in Blocks of consciousness and the unbroken continuum, eds B. Marley & M. Wastell, Sound 323, London, pp. 96-116.

- Zorn, J 2004, ‘The Game Pieces’, in Audio Culture: readings in modern music, eds C Cox & D Warner, Continuum, London, New York.

Backstory

Baby Reindeer, an iOS app I released in 2011, had run its course. In or around 2018, Apple announced that iOS would no longer support the development platform I originally used. Other professional and personal demands made it impossible to scramble and re-develop using new tools. Baby Reindeer was pulled from the App Store and that was then end of that.

Br2 uses all of the original audio assets of Baby Reindeer plus new material created in early 2020. Revisiting old work can be painful. I wanted to retain the character of the initial release while also digging in to its latent potential. It’s been a balancing act to say the least.

On a purely technical level, game development tools Unity and Wwise have enabled me to “future-proof” the app for continued support on the iOS platform. Br2 is not a game, but develops musically in game-like ways. It extends the original Baby Reindeer sound palette for an even wider variety of potential sonic output and shows the way forward for works yet to come.

Br2 Support

Need help? Have questions?