Ai no Keshiki: sound, light, time & dye

Background

Keshiki in Japanese commonly refers to a scenic view or landscape, but it also refers to the moments of wabi-sabi found in a tea bowl, a whisk, a tea scoop or any of the other tools used in the tea ceremony. These keshiki are often points of unintentional patina accumulated through the process of making or use over time. As moments of sensation created between materials, people, and time, these “views” are both an internal indication and external manifestation of who we are and how we sense the ways in which we change over time.

Overview

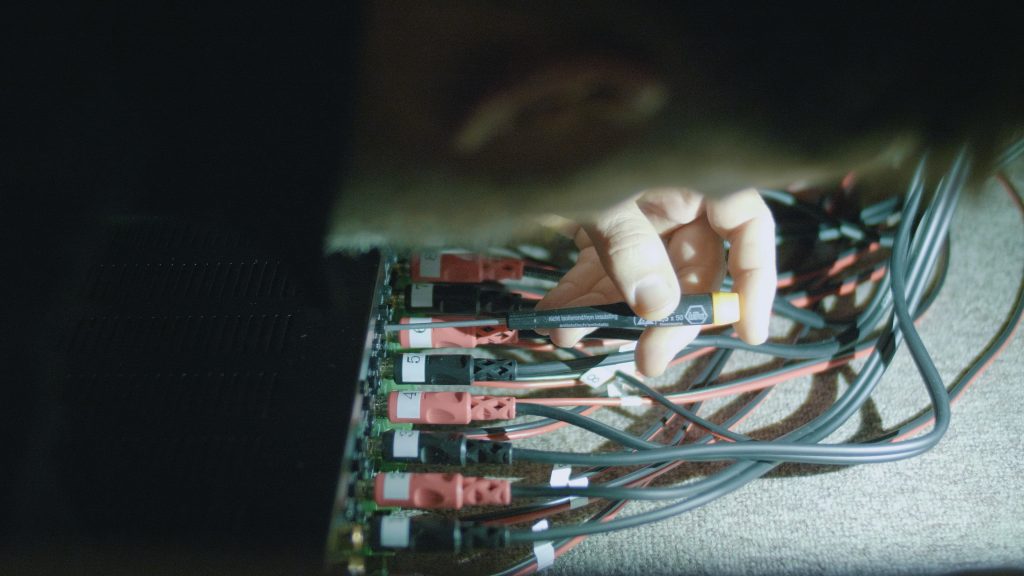

Ai no Keshiki (Indigo Views) is an installation created by Norbert Herber and Rowland Ricketts in conjunction with the Awa Indigo Art Project of Tokushima Prefecture, Japan. The work features over 400 individual pieces of cloth faded by participants over a 6-month period. Indigo enthusiasts from around the world agreed to host boxes in their homes. workspaces, and artist studios. Each box contained a piece of cloth dyed with indigo. On the face was an opening that would allow light to enter the interior of the box and over time, fade the color of the dyed cloth. After a few months of fading, the faded cloth was shipped back to Tokushima and exhibited at Bunka no Mori, an arts center and museum in Tokushima. The fading boxes were repurposed as miniature speaker cabinets. 48 of these were configured into a multichannel array that could “move” individual voices of a larger musical composition across the room where the cloth was hung.

Reflection

In the visual artwork, dye is held in the medium of cloth. Over time, this dye is changed as exposure to light fades the color.

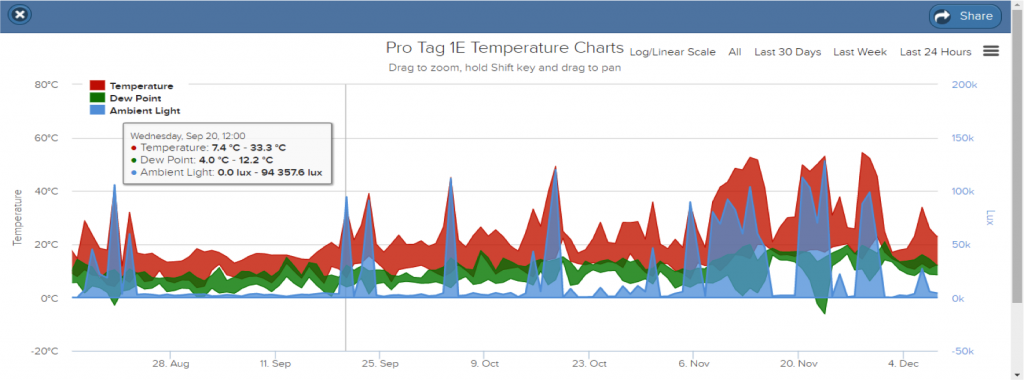

My music (un)intentionally plays in an analogous fashion. Time passes and is marked as tempo, or the rate of beats per minute. Data in the form of ambient light measurements modulates tempo such that bright values increase the tempo and dark values slow it down. All other parameters that shape the sound, including overall event density, event duration, timbre, equalization, and DSP effects are in some way further modulated by shifts of tempo, randomization, weights, and probabilities.

Without getting mired in the semantics and philosophical dimensions of these words,Random is simply that: A random output generated in software. I define Weight as similar to random, but with a defined range of preset outputs. Probability is used in the conventional sense that any given event has x% chance to occur.

Tempo, as directed by light sensor data, is the primary input to a generative music system. Generative is used deliberately in this context so as to make a distinction from Algorithmic music. These approaches have similar means but different ends. In reference to some distinctions set forth by cybernetician Stafford Beer, algorithmic music (by definition) uses a specific set of instructions to achieve a specific goal. Algorithmic music can be developed to compose in a particular style. If you want your music to sound like that of Mr. Mozart or Ms. Oliveros it is possible to create algorithms that can mimic their style down to the last detail. Generative music uses what Beer defines as a heuristic approach, in which one begins with a goal but follows a loose, general set of instructions in order to achieve it. While it is likely that generative music will never be able to sound exactly like Mozart or Oliveros, it is also far more likely to surprise the listener in sonic moments that are novel and unexpected.

Norbert Herber

Tokushima, Japan

January 2018